by Serge Kahili King

There has been some controversy as to whether the ancient Hawaiians ever practiced Huna. One non-Hawaiian writer on Hawaiian spirituality has even claimed that Huna was a word coined by Max Freedom Long, in addition to claiming that that Huna was not a Hawaiian tradition. So let’s examine some Hawaiian and other sources to see what we can find out about this.

There has been some controversy as to whether the ancient Hawaiians ever practiced Huna. One non-Hawaiian writer on Hawaiian spirituality has even claimed that Huna was a word coined by Max Freedom Long, in addition to claiming that that Huna was not a Hawaiian tradition. So let’s examine some Hawaiian and other sources to see what we can find out about this.

First of all, we’ll look at the idea that Max Long coined the word, Huna. In Webster’s Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, 1989 edition, the eighth meaning given for “coin” is “to make, invent or fabricate,” as in to coin a word. Now, Long based his research on the 1865 edition of A Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language by Lorrin Andrews, and in that dictionary we find the word “Huna” with the following definitions:

- to hide or conceal; to keep from the sight or knowledge of another

- to conceal, as knowledge or wisdom

- that which is concealed (In conversation or written sentence this definition would be expressed as “ka huna.”)

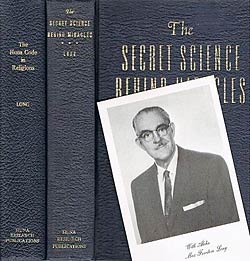

Obviously, Max Long did not coin the word. On page 23 of The Secret Science Behind Miracles he first introduces the word as “the ‘Secret’ ( Huna ),” a perfectly acceptable translation of the idea of hidden knowledge, and later declares that this is the word that he will use to describe the system of Hawaiian esoteric (i.e. secret) knowledge as he understood it. So, regardless of whether or not one agrees with Long’s final version of Hawaiian esoteric knowledge, the fact remains that he did not invent the word or its meaning.

But the question remains, did the Hawaiians themselves use the word Huna to refer to their esoteric knowledge? This is not easy to determine from an oral tradition, but a few knowledgeable Hawaiians wrote some things down about their own traditions after the introduction of written language, and perhaps we may find some clues there.

Many of the ancient heiau or temples of Hawaii held a tall, wooden framework called ‘anu’u that was partially covered with kapa , or bark cloth, which was used for offerings and as a place for priests to reveal the words of the gods. In announcing the revelation they would begin with the phrase, “Let that which is unknown become known.” In Mary Kawena Pukui’s book of Hawaiian proverbs and poetical sayings, Olelo No’eau , we find the same phrase in Hawaiian: Ahuwale ka nane huna . Pukui’s own translation is “That which was a secret is no longer hidden.”

On page 54 of Ka Po’e Kahiko – The People of Old by Samuel Kamakau, in an article published on October 13, 1870, he says that “In the old days in Hawaii, prophetic utterances and hidden sayings ( ‘olelo huna , i.e., speech with secret meaning) were relied on.”

In chapter six of Hawaiian Mythology by Martha Beckwith (University of Hawaii Press, 1970) she relates ideas that her Hawaiian informants told her of twelve sacred islands that in very ancient times lay close to Hawaii and with which there was frequent communication. These islands were inhabited by spirit beings, but humans used to travel back and forth to them (a very shamanic concept). After the great political and religious changes around the middle of the thirteenth century these spirit islands are said to have been rarely seen. They are also said to have been able to move under the sea, on the horizon or into the air like a cloud according to the will of the spirit chief. One of the most famous of these spirit islands is called “Kanehunamoku,” usually translated as “The hidden island of Kane.” “Kane” in this sense was a kind of creator spirit. As for the translation, “The hidden island of Kane” would normally be translated as “MokuhunaoKane” or even “Kanemokuhuna.” The phrase as it appears in ancient chants, “Kanehunamoku,” would be better translated as “Land of the invisible creative spirit.” In Pukui and Elbert’s Hawaiian Dictionary the phrase po’o huna is translated as “mysterious, hidden, invisible, as the gods,” so rendering “Kanehuna” as “invisible Kane” is a valid translation. All of this is significant because there are many tales of “Kanehunamoku” in which humans travel there, learn esoteric knowledge (i.e., knowledge of arts and crafts unknown to humans before then) and return to share that knowledge with the rest of humanity.

The following chant by Edith Kanaka’ole is very clear in its use of the word huna:

E ho mai i ka ‘ike mai luna mai e

O na mea huna no’eau o na mele e

E ho mai, e ho mai, e ho mai e

Grant us knowledge from above

The things of knowledge hidden in the chants

Grant us these things

Further intensive research could probably turn up more instances in which the word “Huna” was actually used by Hawaiians in reference to secret or esoteric knowledge, even without resorting to the word kahuna with all its roots and implications. That “ka ‘ike huna,” the esoteric knowledge of using the power of the mind to influence nature and events was practiced by the Hawaiians there is no doubt. References to it are abundant in a great deal of written records. However, this is only a simple article intended to show that Huna was a part of ancient Hawaiian culture.

I will end by listing seven proverbs from the book by Pukui mentioned above which also show that the ancient Hawaiians were aware of the Seven Principles that were taught to me by my hanai Hawaiian uncle, William Wana Kahili. He called what he taught me ka ‘ike huna, but that was not intended as a title. Calling this knowledge “Huna” was my idea, and I regret all the confusion it has caused, because it is not related to Long’s teachings at all. When I asked my uncle if I should call it that for teaching purposes, all he said was “the knowledge is the knowledge whatever you call it.”

- ‘A’ohe pau ka ‘ike i ka halau ho’okahi , “All knowledge is not taught in one school,” a variation on the idea that there are many sources of knowledge and many ways to think about things. Therefore, “The world is what you think it is.”

- ‘A’ohe pu’u ki’eki’e ke ho’a’o ‘ia e pi’i , “No hill is too high to be climbed,” a way of saying that nothing is impossible and that “There are no limits.”

- He makau hala ‘ole , “A fishhook that never fails to catch,” said of one who always gets what he wants. The fishhook was a primary symbol of concentrated attention, and a good fishhook could attract fish even without bait. So, “Energy flows where attention goes.”

- Wela ka hao! , “Do it now!” In other words, “Now is the moment of power.”

- He ‘olina leo ka ke aloha, “Joy is in the voice of love.” Or, “To love is to be happy with…”

- Aia no i ka mea e mele ana , “Let the singer select the song,” a poetic way of acknowledging that “All power comes from within.

- ‘Ike ‘ia no ka loea i ke kuahu , “An expert is recognized by the altar he builds.” As Pukui puts it, “It is what one does and how well he does it that shows whether he is an expert.” Put a different way, “Effectiveness is the measure of truth.”